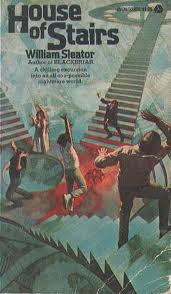

House of Stairs may be one of the most disturbing and memorable young adult science fiction books ever. I first encountered it in junior high, and it left a chill that has never completely left. Written in the 1970s, in a period of deep distrust of government, it is a chilling tale of brainwashing, governmental power, distrust, and stairs, terrifying for its bleak visions of humanity and our future.

House of Stairs opens in a chilling, nearly unimaginable environment of, yes, stairs. The place—whatever and wherever it is—contains one endlessly running toilet (apparently with no pipes in either direction, raising still more disturbing questions) providing both drinking water and bathroom facilities (and no privacy), and one small platform—attached to more stairs—with one small screen, and nothing else except stairs. Straight stairs, bent stairs, spiral stairs, some stairs connected by narrow bridges, some stairs connected to nothing at all. Stairs so abundant and yet so confusing that it is nearly impossible to tell where they begin and end, narrow enough to cause genuine fear of constantly falling off, a particular terror since no one can find the bottom.

I don’t know why stairs, in particular, unless the idea is to also enhance physical fitness. We are later told that the entire point was to create a terrifying, cold, comfortless environment, but I can think of other ways to accomplish this without wrecking people’s knees or creating a near constant risk of a broken neck. My best guess is that William Sleator had a nightmare about stairs and decided to weave it into this dystopian tale. It certainly works to create a nightmarish feeling.

Left on the stairs are five teenagers: Peter, Lola, Blossom, Abigail and Oliver. Peter is a shy, nearly inarticulate kid who is almost certainly gay (and an implied, not stated survivor of sexual/physical abuse); Lola a teenage rebel; Blossom an indulged and fat mean rich kid; Abigail a pretty girl determined to please everyone to keep herself from getting hurt; and Oliver a popular jock. None of them have any idea why they are there (although in the case of the first three, it seems clear that they were chosen because of their inappropriate social behavior, and this may be true for the other two as well.) They can only see the infinite stairs, and the screen, and know that they are hungry. Very hungry. And that they can fall off the stairs at any time.

And that if they do the right things—whatever the right things are—the machine will reward them with food. Otherwise, they will starve.

Sleator shifts from viewpoint to viewpoint in each chapter, creating five distinct personalities. The five kids are introduced as stereotypes, but none stay that way: even Blossom the mean girl turns out to have unexpected depths. Abigail and Oliver begin a strange, twisted relationship that is half pure teenager, half terror. Blossom, Oliver and Lola vie for control of the group, Blossom with lies and gossip; Oliver with force; Lola with desperate logic and intelligence. Lola manages to detox from cigarettes and get into shape through jogging on the stairs. (Since first reading this book, I have now had the fun of living with someone quitting smoking cold turkey, and let me tell you, a good half of the kids’ problematic issues can probably be blamed on Lola’s nicotine withdrawal alone.) Peter retreats more and more into his fantasy world, the only small comfort he has, beyond the food.

In side conversations, the five kids reveal the daily horrors of their pre-stair lives, in what is apparently a future United States. (This isn’t directly stated, but several references to a President are made.) As children, the sexes are severely segregated—even the independent, outsider rebel Lola admits that she has never been alone with a boy, and Blossom is horrified by the very thought, while Oliver and Abigail feel extreme shame and uncertainty at being alone with the opposite sex and Peter oddly seems to have no thought of it at all. Books have nearly vanished, replaced by screens tailored to scroll by at the exact speed you are reading, and which contain stuff, according to the not overly intelligent Abigail, more interesting than books. (Peter likes books because, as he notes, you can become lost in them.) Nearly everyone lives in enormous, dreaty, industrial block housing. The few exceptions—the very wealthy—live in houses with, gasp, separate rooms for eating and cooking and even own the occasional real tree. They are kept strictly segregated from everyone else, to ensure that no one else learns that individual houses still exist. Orphans abound. Suddenly, the house of stairs is not sounding as bad.

Between conversations like this, the screen begins to train the kids to dance upon command, giving them just enough food to survive, not enough to satisfy. (And almost certainly not enough to prevent them from getting various vitamin deficiencies—the food served is meat, and the book never mentions other substances, but does mention that none of the kids are looking all that well.)

And then the machine encourages them to turn on one another. Hit, betray, lie—and be rewarded with food. Refuse, and starve.

And yet, despite the hunger, the terror, and the endless stairs, two of the five kids manage to resist, to fight. Not surprisingly, these are the two who had the most problems adjusting to real world society: Lola and Peter. As even Abigail, not the most perceptive person, notes, Lola has rarely cared what anyone thinks about her, and even here, on the stairs, where her ability to eat is completely dependent on four other people performing a proper dance and being willing to share food with her, she still doesn’t care much. And Peter can simply retreat into his fantasy world. I like that the rebel and the loser are the two able to resist, to fight conformity, while the nice girl, the jock and the mean girl all fail to resist. Even if it means that they do nearly starve to death, rescued only at the very last minute by an elevator and a lot of IVs.

I have said that this is all chilling and terrifying, and it is, but in some ways, the last chapter, which explains everything as part of an elaborate experiment, is even more chilling. By then, thanks to their conditioning, none of the five can tell the difference between the colors of red and green. They can only see a light. The thought that anyone could train me not to see colors terrified me then and terrifies me now.

A related horror: although it’s not entirely surprising that both Oliver and Blossom, who display a strong streak of nastiness even before the machine begins training the kids to be cruel, end up falling completely under its influence, it is terrifying that Abigail, who begins as a rather nice girl, becomes so utterly nasty and cruel. She is, of course, driven by hunger, and it is clear that she was the sort to follow the crowd and not make waves before this; nonetheless, to see a nice person turned evil is distressing.

Sleator’s detailed, clinical description of how easily people can be broken—coupled with Lola’s insights on other training methods—is all too believable. It is, I suppose, a small comfort to learn at the end that even the three conditioned kids are going to be fairly useless spies. (The shaking and fear of the experiment’s director also suggests that some serious questions are about to be asked—mostly, I should note, because the experiment does not succeed.)

As readers, we are meant, I think, to identify with Lola and Peter, while recognizing that some of us, at least, probably have some of Abigail and Blossom, and perhaps Oliver in us as well. (I say perhaps Oliver because he is the only one of the five that I really couldn’t identify with.) Abigail’s need to conform, to not upset people, to be politely skeptical, is all too human.

And, oh, yes, Blossom.

Blossom is a Mean Girl, and yes, she was almost certainly a Mean Girl even before her parents died, back when she had everything. She doesn’t hesitate to blab state secrets to two kids that she’s known for all of fifteen minutes. She gossips, she lies, her desperation for food leads her to interrupt the food distribution, leaving the others hungry. What she does to Lola and Peter and Abigail and Oliver is beyond despicable. Her constant whining and blaming of others is grating. And yet.

She is also a 16 year old who, one month before her arrival, lived a life of privilege and excellent food, which she has lost partly, I assume, because of her attitude (and the results of whatever testing done on her, tests that undoubtedly revealed her mean streak), but also partly because her parents died. As her inner monologue reveals, she needed, desperately needed, something to hate, since she has not been allowed to grieve, or blame whatever killed her parents. (The text doesn’t say, but I get the distinct impression the death was not as accidental as Blossom claims.)

As Lola notes, Blossom is not originally as helpless as she appears; indeed, she may be one of the most clever of the group. She does what she can to survive. The terror is seeing what she’s willing to do to achieve those goals—and how easily a group of scientists can enable her to do so.

I have one lingering question: where exactly did the experimenters build these stairs? The compound, by its description, is a huge place, and four of the kids confirm that the United States of this book does not exactly have a lot of free space available. And exactly how is the water running to and from that toilet? (As a kid, I figured they should be able to follow the water pipes to a wall someplace and from there find their way out, but that never happens.) An optical illusion effect covering up the pipes?

I don’t know. All I do know is that this is a book whose stairs and ending linger long in the memory.

With a horrific description of just what depths hunger will lead you to.

Housekeeping note: The Madeleine L’Engle reread starts next month with And Both Were Young. I’ll be rereading the books in publication order, and in a slightly new touch, I’ll be looking at some of L’Engle’s mainstream fiction work along with her science fiction/fantasy.

Mari Ness didn’t even want to look at stairs for days after finishing this book.